Over the course of this class, we’ve discussed and analyzed many famous Italian authors who are widely regarded as some of the greats within their field. However, while these authors remain influential today, their works were published at a point in history where women were generally considered to be inferior to men and were often forced into lesser roles in society. As a result of this, we can see the influence of gender roles and its impact on the representation of women in Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’, Boccaccio’s ‘The Decameron’, and Petrarch’s ‘Canzoniere’.

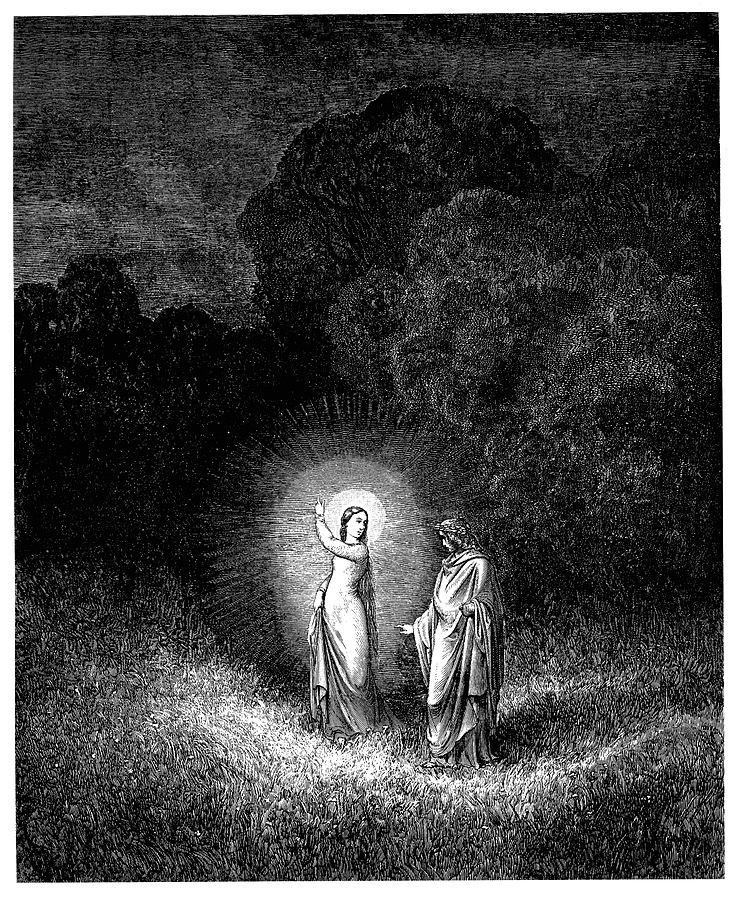

‘The Divine Comedy’ focuses on the journey that Dante, the pilgrim, takes through Hell, Purgatory, and eventually Heaven (referred to as ‘Paradise’ within the text). Over the course of this journey, Dante speaks to countless souls that have moved on to the afterlife and writes about their stories. However, men tend to dominate these conversations while women are sidelined. In fact, there are only two significant women in ‘The Divine Comedy’ that we discussed: Francesca and Beatrice. Francesca first appears in Canto 5, which centers around the second circle of Hell – lust; Dante asks Francesca and Paolo ended up being damned, to which Francesca recounts the story of reading ‘Lancelot du lac’ with her lover and that “one point alone was the one that overpowered us” (canto 5, lines 131-132). While Dante feels pity for the couple, as apparent from him fainting as the canto ends, he still believes that they should be punished for their love. In canto 3, the gates of Hell read “Justice moved my high maker; divine power made me, highest wisdom, and primal love” (Canto 3, lines 4-6), which makes it evidently clear that Dante believes all souls in Hell deserve their punishment, no matter how much pity he feels. On the other hand, we have Beatrice, who plays a significant role in Dante’s literature as a whole. In ‘The Divine Comedy’, Beatrice is the woman who made Dante’s journey possible in the first place. As opposed to Francesca, who Dante shuns for her sin, Beatrice is the exact opposite; he reveres Beatrice as graceful, beautiful, and holy. This is especially evident once we reach ‘Paradiso’, as Beatrice is the woman who allows Dante to come into contact with God, which is shown in the quote “The role that Dante assigns to her is reminiscent of the role that Christ plays in allowing humans to know God and achieve Heaven” (Carey, 2007, p.93). The portrayal of these two women are obviously very different, which makes it clear that Dante believes women should embody purity like Beatrice, and that those like Francesca who do not, should be punished.

On the other hand, we have ‘The Decameron’ which features several stories centering around women. As opposed to Dante, Boccaccio depicts many strong, witty women that are able to stand up for themselves despite the stigma around doing so at the time. A prime example of this is seen in the story of the Madonna Filippa, which is the 7th story of the 6th day; This story centers around Filippa, who is caught cheating on her husband and is then taken to trial, where she could be put to death if found guilty. Instead of denying her crime, she admits to the judge that she was guilty of adultery and defends her actions by stating that she’s never denied her husband anything, that she simply has surplus love to give and asks the judge “Am I to cast it to the dogs? Is it not much better to bestow it on a gentleman that loves me more dearly than himself, than to suffer it to come to nought or worse?” (line 17). Seemingly through her wit alone, she’s able to get the crowd and judge on her side, and gets the law changed such that only women who commit adultery for money are punished. However, upon further inspection, this story isn’t as empowering as it seems. Firstly, while many women in The Decameron stand up for themselves (which was revolutionary in literature at the time), they generally don’t challenge specific laws or roles placed on women by society. This rings true for Filippa as well. She does challenge the law on her own, but even after her defense, it remains put in place and is only changed such that “thenceforth only such women as should wrong their husbands for money should be within its purview” (line 18); Filippa is only able to change the law to fit her given circumstances rather than calling for the abolition of said statute, or to have men included in it’s punishment. Additionally, Boccaccio seems to allude that Filippa’s beauty played a big part in her success. As Marcel Janssens states, women in The Decameron are often able to succeed in defending themselves “provided she is beautiful, witty, and tricky” (Wright, 1991, p. 27), and Filippa falls into this category as well. Early on in this story, it’s stated that Filippa’s beauty and poised nature caused the judge to feel sympathetic towards her, as shown in the quote “The Podestà, surveying her, and taking note of her extraordinary beauty, and exquisite manners, and the high courage that her words evinced, was touched with compassion for her” (line 11). While Filippa made a compelling argument that was able to get the crowd on her side, the prior quote begs the question: If Filippa did not have her “extraordinary beauty”, would she have been as successful?

Finally, we have Petrarch, whose work is unique as it only focuses on one woman: Laura. Despite nearly all of Petrarch’s poems being centered around his love for Laura (even after her death), she never actually speaks in any of his work. Instead, Petrarch decides to speak about her and describe how much he loves her, rather than depicting any direct interactions the two may have had. Similar to the depictions of Beatrice in ‘The Divine Comedy’, Petrarch describes Laura as if she’s a holy figure rather than a normal woman. This is especially seen in sonnet 90, where he states “The way she walked was not the way of mortals but of angelic forms;” (lines 9-10) and refers to her as “a godly spirit and a living sun” (line 12). While Petrarch clearly loves Laura deeply and praises her highly, this does little to let the reader know who she was as a person in real life. Due to Laura’s lack of a voice within the text, Nancy Vickers points out that “bodies fetishized by a poetic voice logically do not have a voice of their own; the world of making words, of making texts, is not theirs” (Cox, 2005, p. 3). Ultimately, Petrarch’s depiction of Laura is one that many women deem to be fetishizing, as she seemingly has no thoughts or words of her own and is only seen through the eyes of the poet.

Overall, Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch are all very influential authors, and their works should still be taught and read today due to how much they’ve impacted literature as we know it. However, it’s also important to note that these works were products of their time, which is evidently clear from how each author portrays women; ranging from Boccaccio’s depiction of women who use their wits and beauty to get what they want, to Petrarch and Dante’s love interests who embody holiness.

Citations:

- Dante, A. D. (1996). The divine comedy of dante alighieri : Inferno. Oxford University Press USA – OSO.

- Carey, Brooke L., “Le Donne di Dante: An Historical Study of Female Characters in The Divine Comedy” (2007). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 573. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/573

- Decameron web. Decameron Web | Texts. (2010, February 15). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/dweb/texts/DecShowText.php?myID=nov0607&lang=eng

- WRIGHT, E. C. (1991). Marguerite Reads Giovanni: Gender and Narration in the “Heptaméron” and the “Decameron.” Renaissance and Reformation / Renaissance et Réforme, 15(1), 21–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43445607

- Cox, V. (2005). Sixteenth-century women Petrarchists and the legacy of Laura. Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.projectcontinua.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/16th-C-Women-Petrarchists-and-the-Legacy-of-Laura.pdf

- Petrarca, Francesco, Selected Poems from the Canzoniere

- Antonio Salamanca (1500-62) – Laura and Petrarch. Royal Collection Trust. (n.d.). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.rct.uk/collection/809553/laura-and-petrarch

- Gustave Doré – Dante Alighieri – Inferno – plate 7 (Beatrice Stock Photo. Alamy . (n.d.). Retrieved December 23, 2021, from https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-gustave-dor-dante-alighieri-inferno-plate-7-beatrice-137875413.html